The Battle of Leyte Gulf Underscored Japan s Ability to Continue Its Defense of the Philippines

World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. However, the half century that now separates us from that conflict has exacted its toll on our collective knowledge. While World War II continues to absorb the interest of military scholars and historians, as well as its veterans, a generation of Americans has grown to maturity largely unaware of the political, social, and military implications of a war that, more than any other, united us as a people with a common purpose.

Highly relevant today, World War II has much to teach us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations in the coalition war against fascism. During the next several years, the U.S. Army will participate in the nation's 50th anniversary commemoration of World War II. The commemoration will include the publication of various materials to help educate Americans about that war. The works produced will provide great opportunities to learn about and renew pride in an Army that fought so magnificently in what has been called "the mighty endeavor."

World War II was waged on land, on sea, and in the air over several diverse theaters of operation for approximately six years. The following essay is one of a series of campaign studies highlighting those struggles that, with their accompanying suggestions for further reading, are designed to introduce you to one of the Army's significant military feats from that war.

This brochure was prepared in the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Charles R. Anderson. I hope this absorbing account of that period will enhance your appreciation of American achievements during World War II.

GORDON R. SULLIVAN

General, United States Army

Chief of Staff

By the summer of 1944, American forces had fought their way across the Pacific on two lines of attack to reach a point 300 miles southeast of Mindanao, the southernmost island in the Philippines. In the Central Pacific, forces under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commanding the Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean areas, had island-hopped through the Gilberts, the Marshalls, and the Carolines. More than 1,000 miles to the south, Allied forces under General Douglas MacArthur, commanding the Southwest Pacific area, had blocked the Japanese thrust toward Australia, and then recaptured the Solomons and New Guinea and many of its outlying islands, isolating the huge Japanese base at Rabaul.

These victories brought American forces to the inner defensive line of the Japanese Empire, and in the summer of 1944 they pushed through that barrier to take the Marianas, the Palaus, and Morotai. With the construction of airfields in the Marianas, US. Army Air Forces were within striking distance of the Japanese home islands for the first time during the war. Yet, despite an unbroken series of defeats during two years of fighting, the Japanese showed no inclination to end the war. As American forces closed on Japan, they thus faced the most formidable outposts of the Japanese Empire: the Philippines, Formosa, and Okinawa.

Months before the Marianas and Palaus came under American control, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had addressed the question of objectives beyond those island groups. Early discussions considered Formosa and the Philippines. Domination of either would threaten Japanese sea lines of communication between her fleet bases and industries in the home islands and the resource-rich East Indies to the south. In addition, a strong American beachhead in the Philippines would jeopardize Japan's internal communications within the archipelago, the location of the largest concentration of Japanese ground strength outside the home islands and China. Although possession of Formosa would give American forces an ideal springboard for operations on the Chinese mainland it would place those forces between Japan and the huge enemy garrison in the Philippines. The Philippine archipelago thus seemed a more logical objective.

t.jpg)

t.jpg)

The Joint Chiefs of Staff could not afford to ignore the political implications of its military planning. A return to the Philippines involved a compelling political dimension that did not apply to Formosa. The Philippine Islands had been a special concern of the United States since 1898, and the inherent politico-military responsibilities arising from that relationship could not be discarded so easily. General MacArthur and others insisted that the United States had a moral obligation to liberate the Republic's 16 million citizens from harsh Japanese occupation as soon as possible.

On 12 March 1944, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directed General MacArthur to plan an invasion of Mindanao, the southernmost island of the archipelago, starting on 15 November. The general responded in June with a two-phase operational plan which included the seizure of southern Mindanao on 25 October to serve as a staging area for a larger amphibious assault against Leyte three weeks later. Luzon, the largest island in the archipelago and the location of the headquarters for Japanese forces in the islands, would eventually have to be taken to secure the Philippines. However, Mindanao and Leyte had features that made them desirable, if not necessary, preliminary operations to the liberation of Luzon. For one, both islands were accessible. Generally exposed coastlines-Mindanao to the south and Leyte to the east-would allow American forces approaching from either direction to preserve uninterrupted lines of communication from recently secured bases. In contrast, an amphibious strike directly against Luzon in the northern Philippines would be more difficult to support. Second and critical to forces operating together for the first time, both islands were known to be defended by garrisons much smaller than that on Luzon. MacArthur's staff estimated Japanese combat strength on Mindanao to be 50,000 with another 50,000 in the Visayas, the central Philippine Islands which included Leyte. They estimated that Luzon had 180,000 defenders.

Preparation for the invasion of the Philippines was greatly assisted by ULTRA, the Allied top secret interception, decryption, and dissemination program against Japanese radio traffic. Acting on tip-offs from ULTRA, American submarines and aircraft had been ambushing Japanese shipping in the Western Pacific and interfering with enemy exploitation of resources in the East Indies for many months. In June 1944 ULTRA revealed that Tokyo had decided to greatly strengthen its Philippine defenses to block the expected American route of advance northward toward the home islands. That knowledge and subsequent intercepts had allowed the Allied high command to focus submarine and air attacks against Japanese shipping routes and flight paths to

the Philippines. But despite increasing losses, the Japanese buildup in the islands continued through the summer and fall of 1944.

For the Allies, the sooner the invasion began, the better. But the availability of amphibious shipping, fleet fire support, and air support became major obstacles to accelerating the invasion date. Logistical studies by different headquarters gave conflicting answers to the question of whether or not there was enough shipping in the Pacific to support major landings on both Mindanao and Leyte. By the end of summer the Joint Chiefs of Staff could no longer wait to fix the timetable for the assault. On 8 September the chiefs directed MacArthur and Nimitz to take the Leyte and Surigao Strait area beginning 20 December.

The issues of objectives and operational scheduling were finally settled by fleet-covering operations in support of the invasion of the Palaus and Morotai. Beginning on 7 September 1944, carrier task forces from Admiral William F. Halsey's Third Fleet struck Yap and the Palaus, as well as Mindanao and islands in the central Philippines. Air strikes continued in October against Japanese airfields on Okinawa, Formosa, and Luzon, as well as enemy shipping in adjacent waters. American planners estimated that these attacks destroyed more than 500 enemy aircraft in the Philippines and a similar number elsewhere, in addition to about 180 seagoing merchant ships. The aerial successes convinced them that a major landing on Mindanao was no longer necessary and that available shipping and logistical strength could now be concentrated on Leyte. Accordingly, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directed MacArthur and Nimitz to cancel intermediate operations and accelerate planning to carry out an invasion of Leyte on 20 October.

Meanwhile, Japanese Imperial headquarters received a completely different impression of what had been occurring. With their naval pilots forwarding wildly exaggerated reports of downing 1,200 American aircraft and sinking eleven aircraft carriers, Tokyo became increasingly optimistic. Although senior naval officers grew suspicious of these claims, other military authorities in Tokyo accepted them. In their eyes, the supposed American losses made it possible to decisively defeat the Americans wherever they landed in the Philippines-if Japan could concentrate its resources there. American planners, however, continued to regard Leyte as a mere stepping stone to the more decisive campaign for Luzon. This conceptual difference would greatly increase the stakes at Leyte or wherever the Americans landed first.

One of the larger islands of the Philippine archipelago, Leyte extends 110 miles from north to south and ranges between 15 and 50 miles in width. The land surface presented features both inviting and forbidding to U.S. military planners. Deep-water approaches on the east side of the island and sandy beaches offered opportunities for amphibious assaults and close-in resupply operations. The interior of the island was dominated by a heavily-forested north-south mountain range, separating two sizable valleys, or coastal plains. The larger of the two, Leyte Valley extends from the northern coast to the long eastern shore and at the time, contained most of the towns and roadways on the island. Highway 1 ran along the east coast for some forty miles between the town of Abuyog to the northern end of San Juanico Strait between Leyte and Samar Islands. The roads and lowlands extending inland from Highway 1 provided avenues for tank-infantry operations, as well as a basis for airfield construction.

The only other lowland expanse, Ormoc Valley is on the west side of the island connected to Leyte Valley by a roundabout and winding road. From the town of Palo on the east coast, Highway 2 ran west and northwest through Leyte Valley to the north coast, then turned south and wound through a mountainous neck to enter the north end of Ormoc Valley. The road continued south to the port of Ormoc City, then along Leyte's western shore to the town of Baybay. There it turned east to cross the mountainous waist of the island and connected with Highway 1 on the east coast at Abuyog. Below Abuyog and Baybay, the mountainous southern third of Leyte was only sparsely inhabited and contained no areas suitable for development.

Mountain peaks reaching to over 4,400 feet as well as the jagged outcroppings, ravines, and caves typical of volcanic islands offered formidable defensive opportunities. In addition, the late-year schedule of the assault would force combat troops and supporting pilots, as well as logistical units, to contend with monsoon rains. On a favorable note, the population of over 900,000 people, most of whom engaged in agriculture and fishing, could be expected to assist an American invasion, since many residents already supported the guerrilla struggle against the Japanese in the face of harsh repression.

The Imperial Japanese Army administered all garrisons and forces in the Pacific and Southeast Asia through its Southern Army, which included four area armies, two air armies, and three garrison armies. The 14th Area Army was responsible for the defense of the Philippines. Commanded by General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the 14th

Area Army delegated responsibility for defense of Mindanao and the Visayas to the 35th Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Sosaku Suzuki. From an order of battle that included four complete divisions and elements of another, plus three independent mixed brigades, Suzuki assigned the 16th Division, under Lt. Gen. Shiro Makino, to defend Leyte and designated the 30th Division, posted to Mindanao, as field army reserve. By October Japanese strength in the Philippines, including air and construction units, totaled about 432,000 troops, with General Makino's 16th Division controlling somewhat over 20,000 soldiers on Leyte.

The 14th Area Army was supported by sizeable air and naval forces. Both the 4th Air Army and the 1st Air Fleet were headquartered in the Philippines, and could call on reinforcement from task forces in the Borneo and Formosa areas totaling 4 carriers, 7 battleships, 2 battleship-carriers, 19 cruisers, and 33 destroyers. American intelligence estimated the Japanese still had between 100 and 120 operational airfields in the Philippines, with 884 aircraft of all types. The largest of six airfields on Leyte-at Tacloban, the provincial capital-could accommodate medium bombers.

To take Leyte, American and Allied forces mounted the largest amphibious operation to date in the Pacific. The Joint Chiefs of Staff designated General MacArthur supreme commander of sea, air, and land forces drawn from both the Southwest Pacific and Central Pacific theaters of operation. Allied naval forces consisted primarily of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, commanded by Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid. With 701 ships, including 157 warships, Kinkaid's fleet would transport and put ashore the landing force.

The U.S. Sixth Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, and consisting of two corps of two divisions each, would conduct operations ashore. Maj. Gen. Franklin C. Sibert's X Corps included the 1st Cavalry Division and the 24th Infantry Division, the latter less the 21st Infantry, which had been temporarily organized as an independent regimental combat team (RCT). Maj. Gen. John R. Hodge's XXIV Corps included the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions, the latter less the 381st Infantry, also organized as an RCT in army reserve. The Sixth Army reserve would include the 32d and 77th Infantry Divisions and the 381st RCT. Of the six divisions, only the 96th Infantry Division had not yet seen combat.

Supplementing these forces were a battalion of Rangers and a support command specially tailored for large amphibious operations. The task of the 6th Ranger Infantry Battalion was to secure outlying islands and guide naval forces to the landing beaches. The new Sixth Army

Service Command (ASCOM), commanded by Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Casey, was responsible for organizing the beachhead supplying units ashore, and constructing or improving roads and airfields. General Krueger had under his command a total of 202,500 ground troops.

Air support for the Leyte operation would be provided by the Seventh Fleet during the transport and amphibious phases, then transferred to Allied Air Forces, commanded by Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, when conditions ashore allowed. More distant-covering air support would be provided by the four fast carrier task forces of Admiral Halsey's Third Fleet, whose operations would remain under overall command of Admiral Nimitz.

The Sixth Army mission of securing Leyte was to be accomplished in three phases. The first would begin on 17 October, three days before and some fifty miles east of the landing beaches, with the seizure of three islands commanding the eastern approaches to Leyte

t.jpg)

Gulf. On 20 October, termed "A-day," the X and XXIV Corps would land at separate beaches on the east coast of Leyte, the former on the right (north), the latter fifteen miles to the south. As quickly as possible, the X Corps would take the city of Tacloban and its airfield both just one mile north of the corps beachhead secure the strait between Leyte and Samar Islands, then push through Leyte Valley to the north coast. The XXIV Corps' mission was to secure the southern end of Leyte Valley for airfield and logistical development. Meanwhile, the 21st RCT would come ashore some seventy miles south of the main landing beaches to secure the strait between Leyte and Panaon Islands. In the third phase, the two corps would take separate routes through the mountains to clear the enemy from Ormoc Valley and the west coast of the island at the same time placing an outpost on the island of Samar some thirty-five miles north of Tacloban.

Preliminary operations for the Leyte invasion began at dawn on 17 October with minesweeping operations and the movement of the 6th Rangers toward three small islands in Leyte Gulf. Although delayed by a storm, the Rangers were on Suluan and Dinagat by 1230. On Suluan they dispersed a small number of Japanese defenders and destroyed a radio station, while they found no enemy on Dinagat. On both, the Rangers proceeded to erect navigation lights for the amphibious transports to follow three days later. The Rangers occupied the third island Homonhon, without opposition the next day. Meanwhile, reconnaissance by underwater demolition teams revealed clear landing beaches for assault troops on Leyte itself.

Following four hours of heavy naval gunfire on A-day, 20 October, Sixth Army forces landed on assigned beaches at 1000 hours. Troops from X Corps pushed across a four-mile stretch of beach between Tacloban airfield and the Palo River. Fifteen miles to the south, XXIV Corps units came ashore across a three-mile strand between San José and the Daguitan River. Troops in both corps sectors found as much or more resistance from swampy terrain as from Japanese fire. Within an hour of landing, units in most sectors had secured beachheads deep enough to receive heavy vehicles and large amounts of supplies. Only in the 24th Division sector did enemy fire force a diversion of follow-on landing craft. But even that sector was secure enough by 1330 to allow General MacArthur to make a dramatic entrance through the surf and announce to the populace the beginning of their liberation: "People of the Philippines, I have returned! By the grace of Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil."

By the end of A-day, the Sixth Army had moved inland as deep as two miles and controlled Panaon Strait at the southern end of Leyte. In

the X Corps sector, the 1st Cavalry Division held Tacloban airfield and the 24th Infantry Division had taken the high ground commanding its beachheads Hill 522. In the XXIV Corps sector, the 96th Infantry Division held the approaches to Catmon Hill, the highest point in both corps beachheads; the 7th Infantry Division had taken the town of Dulag, forcing General Makino to move his 16th Division command post ten miles inland to the town of Dagami. These gains had been won at a cost of 49 killed 192 wounded and 6 missing.

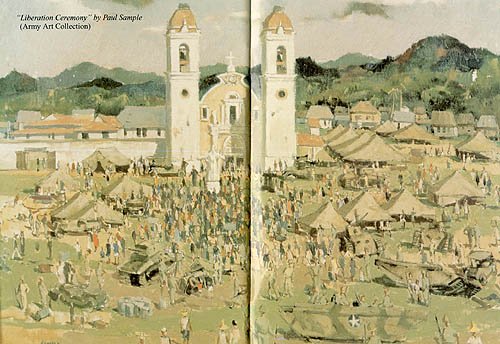

In the days that followed the Sixth Army made steady progress inland against an enemy which resisted tenaciously at several points but was unable to coordinate an overall island defense. In the process, the 1st Cavalry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Verne D. Mudge, secured the provincial capital of Tacloban on 21 October. Two days later General MacArthur presided over a ceremony to restore civil

government to Leyte. To prevent a Japanese counterattack from the mountainous interior, the 5th and 12th Cavalry Regiments, 1st Cavalry Brigade, established blocking positions west of the city, while the 7th and 8th Cavalry Regiments, 2d Cavalry Brigade, cleared the fourteen-mile-long San Juanico Strait between Leyte and Samar Islands, mounting tank-infantry advances on one side of the narrow body of water and amphibious assaults and patrols on the other. Opposition was light, and the cavalrymen continued advancing around the northeast shoulder of Leyte toward a rendezvous with the 24th Division.

On the X Corps left, the 24th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Frederick A. Irving, drove inland' meeting more determined enemy resistance. During five days and nights of hard fighting, troops of the 19th and 34th Infantry Regiments killed over 800 enemy in the effort to expand their beachhead and take control of high ground commanding the entrance to the northern Leyte Valley. By 1 November, after a seven-day tank-infantry advance supported by the fire of three

artillery battalions, the division's two regiments had pushed through Leyte Valley and were within sight of the north coast and the port of Carigara. The next day, while the 34th Infantry guarded the southern and western approaches to the port, the 2dCavalry Brigade entered and cleared the city. In the victorious drive through Leyte Valley, the 24th Division killed nearly 3,000 enemy. These advances left only one major port on Leyte-at Ormoc City on the west coast of the island-under Japanese control.

From the XXIV Corps beachhead on the Sixth Army left, General Hodge had sent his two assault divisions into the southern Leyte Valley, the area in which General MacArthur hoped to develop airfields and logistical facilities for subsequent operations against Luzon. The area already contained four airfields and a large supply center.

The mission of the 96th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. James L. Bradley, was to clear the most prominent terrain feature in the entire Sixth Army landing zone, Catmon Hill. From the 1,400foot heights of this promontory, the Japanese had observed and fired on landing craft approaching the beach on A-day. Keeping the enemy on Catmon Hill occupied with intermittent artillery and naval gunfire, Bradley's troops made their way through the swamps south and west of the high ground. On 28 October, the 382d Infantry took a key Japanese supply base at Tabontabon, five miles inland, after a three-day fight in which the Americans killed some 350 enemy. As the battle for Tabontabon raged below, two battalions each from the 381st and 383d Infantry Regiments went up opposite sides of Catmon Hill. The Japanese resisted fiercely, still manning fighting positions after several heavy artillery preparations, but could not stop the tank-supported American advance. By the 31st, when the mop-up of Catmon Hill was completed, American troops had cleared fifty-three pillboxes, seventeen caves, and many other prepared positions.

On the XXIV Corps left, or southern flank, the 7th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Archibald V. Arnold, moved inland against an unusually dense concentration of enemy facilities and defenses. The Japanese had built or improved four airfields in a narrow, ten-mile strip along the east-west road between the small towns of Dulag and Burauen. On 21 October the 184th Infantry took Dulag airfield south of the road while the 32d Infantry cleared both sides of the Calbasag River. Three more days of fighting swamps, extreme heat, and Japanese supported by artillery and armor brought 7th Division regiments to within three miles of Burauen, where three airfields were clustered. The fight for the airfields and village was bloody but flying wedges of American tanks cleared the way for the infantrymen.

In Burauen itself, troops of the 17th Infantry overcame fanatical but futile resistance, with some enemy popping up from spider holes and others making suicidal attempts to stop the American tanks by holding explosives against their armored hulls. One mile north, troops of the 32d Infantry killed more than 400 Japanese at Buri airfield. With two battalions of the 184th Infantry patrolling the corps left flank, the 17th Infantry, with the 2d Battalion, 184th Infantry, attached, turned north toward Dagami, six miles above Burauen. Using flamethrowers to root their enemy out of pillboxes and a cemetery, American troops brought Dagami under control on 30 October, forcing General Makino to move his command post yet further to the west.

While most of its units were occupied in the Dulag-Burauen-Dagami area, the 7th Division also probed across the island. On 29 October, the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry, preceded by the 7th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, moved fifteen miles south along the east coast to Abuyog and then, over the next four days, patrolled west through the mountains to bring Ormoc Bay under observation. Neither advance encountered any Japanese defenders.

As the Sixth Army pushed deeper into Leyte, the Japanese struck back in the air and at sea. On 24 October, an estimated 150 to 200 enemy aircraft, most of them twin-engine bombers, approached American beachheads and shipping from the north. Fifty American land-based aircraft rose to intercept, claiming to have shot down somewhere between sixty-six and eighty-four of the raiders. Nevertheless, day and night air raids continued over the next four days, damaging supply dumps ashore and threatening American shipping. But by 28 October, American air attacks on Japanese airfields on other islands so reduced enemy air strength that conventional air raids ceased to be a major threat.

As Japanese air strength diminished' the defenders began to use a new and deadly weapon, a corps of pilots willing to crash their bomb-laden planes directly into American ships, committing suicide in the process. Termed kamikaze or "divine wind" to recall the 13th century typhoon that scattered and sank a Mongol invasion fleet off southern Japan, these pilots chose as their first target the large American transport and escort fleet that had gathered in Leyte Gulf on A-day. Although Japanese suicide pilots sank no capital ships and only one escort carrier, they damaged many other vessels and filled with foreboding those American soldiers and sailors who witnessed their stunning acts of self sacrifice.

A more serious danger to the American forces developed at sea. To destroy U.S. Navy forces supporting the Sixth Army, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) decided to commit nearly its entire surface fleet to the Leyte Campaign in three major task groups. One, which included four aircraft carriers with no aircraft aboard, was to act as a decoy, luring Admiral Halsey's Third Fleet north away from Leyte Gulf. If the decoy was successful, the other two groups, consisting primarily of heavy surface combatants, would enter the gulf from the west and attack the American transports.

The approach of the surface vessels was revealed on 23 October, when American submarines sank two cruisers. The next day, Seventh Fleet units blocked the southern approaches to Leyte while Third Fleet aircraft began attacking the main surface task force. But when his airmen spotted the four enemy carriers far to the north of Leyte that afternoon, Admiral Halsey took his Third Fleet carriers and battleships in pursuit. That night, the two Japanese surface task forces, unmolested by air attacks, moved toward Leyte Gulf and MacArthur's transports and escort carriers. Seventh Fleet battleships sank or turned back units of the smaller Japanese attack force moving through Surigao Strait south of Leyte. But the second and larger task force, which

t.jpg)

On the morning of 25 October, after two and one half hours of desperate fighting by light U.S. Navy escorts, the Japanese battle fleet mysteriously broke off the engagement and withdrew from the gulf, thereby leaving unexploited the opportunity presented by the Third Fleet's departure. To the north, the Third Fleet caught up with the Japanese carriers and sank all four of them. These encounters, later known as the Battle of Leyte Gulf, represented the largest naval battle in the Pacific. The battle cost the IJN most of its remaining warships, including 3 battleships, one of which was the huge Musashi, 6 heavy and 4 light cruisers, and 9 destroyers, in addition to its remaining carriers.

Americans and Japanese came away from the battle of Leyte Gulf with extremely divergent views of what had occurred. These different assessments provoked planning revisions which completely changed the character and duration of the battle for Leyte. The Americans believed they had dealt the IJN a severe blow; events later proved them correct. But in the immediate aftermath of the sea battle, Japanese commanders believed they had ruined the American carrier force. In fact, they had sunk only one light and two escort carriers and three destroyers. Nevertheless, convinced that they had won a major naval victory and bolstered by reports of air victories in the ten days before A-day, Southern Army resolved to fight the decisive battle on Leyte. Believing MacArthur's ground forces were now trapped on the island, the Japanese command moved to wipe out the Sixth Army. Marshaling available shipping, the Japanese began moving units to Leyte from other islands in the Philippines as well as from Japan and China. The first convoy brought units of the 102d and 30th Divisions during 23-26 October. Over the next six weeks, eight more convoys brought troops from the 1st, 8th, and 26th Divisions, and the 68th Independent Mixed Brigade.

ULTRA intercepts reported the approach of this shipping, but MacArthur's staff at first thought they indicated the beginning of an enemy evacuation. The necessary diversion of Third Fleet and Seventh Fleet aircraft for operations against surviving Japanese fleet units and the incomplete buildup of the U.S. Fifth Air Force on Leyte itself also weakened Allied reconnaissance and offensive capabilities in the immediate vicinity of the battle. Not until the first week in November did MacArthur's staff realize that an enemy reinforcement was under

way. Thereafter, American forces inflicted severe damage on local Japanese merchant shipping, sinking twenty-four transports bound for Leyte and another twenty-two elsewhere in the Philippines, as well as several warships and smaller vessels. By 11 December, however, the Japanese had succeeded in moving to Leyte more than 34,000 troops and over 10,000 tons of materiel, most of it through the port of Ormoc on the west coast.

For both Krueger and MacArthur the Japanese reinforcement caused severe problems. Instead of conducting mop-up operations after clearing the east side of Leyte, the Sixth Army now had to prepare for extended combat in the mountains on its western side. These new preparations included landing three reserve divisions on Leyte, which pushed back General MacArthur's operations schedule for the rest of the Philippine campaign, as well as the War Department's deployment plans in the Pacific.

On the ground the picture still looked bright. The linkup of the 1st Cavalry and 24th Infantry Divisions at Carigara on 2 November closed the highly successful opening drive of the campaign. After seventeen days of combat operations, the Sixth Army had all of its first and second phase objectives under control, as well as one third-phase objective, Abuyog. In addition, elements of the 7th Division had pushed across the island from the southern end of the XXIV Corps sector and controlled approaches to the town of Baybay on the west coast. Only one key area, Ormoc Valley on the west side of the island, remained to be taken.

To clear Ormoc Valley, General Krueger planned a giant pincer operation, with X Corps forces moving south through the mountains and XXIV Corps units pushing north along the western shore. To overcome the expected increased resistance, especially in the mountain barrier to the north, Krueger planned to commit his reserve forces, the 32d and 77th Infantry Divisions, and MacArthur agreed to contribute another, the 11th Airborne.

In this final phase, units of both corps would be operating on terrain much more rugged than that encountered on the eastern coast of the island and in Leyte Valley. North of Ormoc Valley, units of the X Corps would have to make their way south along a ten-mile stretch of Highway 2 through the dense mountainous neck at the northwest shoulder of the island. South of Ormoc Valley, elements of the XXIV Corps would have to advance northward some thirty miles along the coast from Baybay to Ormoc City, all the while under observation of ridgelines only a few hundred yards inland, and then continue north another twelve miles to link up with units of the X Corps. The mountainous terrain north and south of Ormoc Valley offered excellent opportunities for the Japanese to again display the formidable defensive skills for which they were now well known.

For the initial drive on Ormoc Valley, General Sibert's X Corps had the dual missions of opening Highway 2 south through the mountains and closing several other mountain passes through which Japanese forces might counterattack American positions in Leyte

t.jpg)

Valley along the east side of the island. To carry out all these missions, Sibert required additional forces, and on 30 October General Krueger directed General Hodge to return the 21st RCT from the Panaon area to the 24th Division and replace it with a battalion of the 32d Infantry. While awaiting the return of its third regiment, Irving's 24th Division

prepared to sweep the rest of the northern coast before turning south into the mountains.

On 3 November the 24th Division's 34th Infantry moved out from its position two miles west of Carigara. The 1st Battalion soon came under attack from a ridge along the highway. Supported by the 63d Field Artillery Battalion, the unit cleared the ridge, and the 34th Infantry continued unopposed that night through the town of Pinamopoan, halting at the point where Highway 2 turns south into the mountains. Along the five-mile advance west from Carigara, the infantrymen recovered numerous weapons abandoned by the Japanese, including three 75-mm., one 40-mm., and five 37-mm. guns, as well as much ammunition, equipment, and documentation. Then, after a short delay necessitated by Krueger's concern over a possible seaborne Japanese counterattack along Leyte's northern coast, the 24th Division, strengthened by the return of the 21st Infantry, began its drive south.

On 7 November the 21st Infantry went into its first sustained combat on Leyte when it moved into the mountains along Highway 2, less than one mile inland of Carigara Bay. The fresh regiment, with the 3d Battalion, 19th Infantry, attached immediately ran into strong defenses of the newly arrived Japanese 1st Division, aligned from east to west across the road and anchored on fighting positions built of heavy logs and with connecting trench lines and countless spider holes. The entire defense complex soon became known as "Breakneck Ridge."

Three days later, American progress was further impeded by a typhoon, which had begun on 8 November, and heavy rains that followed for several days. Despite the storm and high winds, which added falling trees and mud slides to enemy defenses and delayed supply trains, the 21st Infantry continued its attack. Progress was slow and halting, with assault companies often having to withdraw and attack hills that had been taken earlier. Fortunately, the 2d Battalion, 19th Infantry, had seized the approaches to Hill 1525, two miles east of the road enabling General Irving to stretch out the enemy defenses further across a four-mile front straddling Highway 2.

After five days of battering against seemingly impregnable positions atop heavily jungled hills and two nights of repulsing enemy counterattacks, Irving decided on a double envelopment of the defending 1st Division. He ordered the 2d Battalion, 19th Infantry, to swing east around Hill 1525 behind the enemy right flank, cutting back to Highway 2, three miles south of Breakneck Ridge. To envelop the enemy left flank on the west side of the road Irving sent the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry, over water from the Carigara area to a point two miles west of the southward turn of Highway 2. Lt. Col.

Thomas E. Clifford moved the battalion inland. They crossed one ridge line and the Leyte River, then swung south around the enemy's left flank and approached Kilay Ridge, the most prominent terrain feature behind the main battle area.

Although encountering strong opposition and heavy rains, which reduced visibility to only a few yards, both American battalions had reached positions only about 1,000 yards apart on opposite sides of the highway by 13 November. On that day, Clifford's battalion attacked Kilay Ridge on the west side of the highway while the 2d Battalion, 19th Infantry, assaulted a hill on the east side. Neither unit was able to carry out its objective or close Highway 2.

For two weeks Clifford's men struggled through rain and mud, often dangerously close to friendly mortar and artillery fire, to root the enemy out of fighting positions on the way up the 900-foot Kilay Ridge. But on both Kilay and Breakneck Ridges the Japanese conducted a bitter, skillful defense. On 2 December Clifford's battalion finally cleared the heights overlooking the road and began turning over the area to fresh units of the 32d Division. During the struggle, the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry, lost 26 killed, 101 wounded and 2 missing, but accounted for an estimated 900 enemy dead. For their arduous efforts against Kilay Ridge and adjacent areas, both flanking battalions received Presidential Unit Citations. Clifford himself received the Distinguished Service Cross for the action.

While the struggle for the Kilay Ridge area was taking place, other operations in the X Corps zone proceeded apace. To assist Sibert, General Krueger transferred the 32d Division to the X Corps on 14 November; Sibert in turn began replacing the exhausted units of the 24th Division with those of the 32d, commanded by Maj. Gen. William H. Gill. Meanwhile, operating east of the Breakneck-Kilay Ridge area, the 1st Cavalry Division had fought its way southwest of Carigara through elements of the defending 102d Division to link up with 32d Division infantrymen near Highway 2 on 3 December. But it was not until 14 December that the two divisions finally cleared all of the Breakneck-Kilay Ridge area, placing the most heavily defended portions of Highway 2 between Carigara Bay and the Ormoc Valley under X Corps control.

Throughout this phase, American efforts had become increasingly hampered by logistical problems. Mountainous terrain and impassable roads forced Sixth Army transportation units to improvise resupply trains of Navy landing craft, tracked landing vehicles, airdrops, artillery tractors, trucks, even carabaos and hundreds of barefoot Filipino bearers. Not surprisingly, the complex scheduling of this jerry-built system slowed resupply as well as the pace of assaults, particularly in the mountains north and east of Ormoc Valley and subsequently in the ridgelines along Ormoc Bay.

While the X Corps was making its way through the northern mountains, the XXIV Corps had been attempting to muster forces around Baybay for its drive north along the west coast through the Ormoc Valley. Yet, in mid-November the XXIV Corps still had only the 32d Infantry in western Leyte, with the remainder of the 7th Division still securing the Burauen area. Only the arrival of the 11th Airborne Division on Leyte in strength around the 22d allowed the corps commander, General Hodge, to finally shift Arnold's entire 7th

Division to the west. But almost immediately, further delays ensued. As the 32d Infantry consolidated the division's jump-off positions about ten miles north of Baybay, it suddenly came under attack by the Japanese 26th Division on the night of 23 November. The regiment's 2d Battalion was pushed back, then regained lost ground the next day. To prevent another setback, General Arnold attached the 1st Battalion, 184th Infantry, to the 32d Infantry. Also supporting the American defensive effort was a platoon from the 767th Tank Battalion, two 105mm. batteries from the 49th Field Artillery Battalion, and one Marine Corps 155-mm. battery. The larger caliber unit was from the 11th Gun Battalion, one of two Marine Corps artillery battalions originally scheduled for the invasion of Yap but transferred to Sixth Army control when that operation was canceled. Pummeled by heavy fire from these artillery units, the Japanese went straight for them the night of the 24th, putting four 105-mm. pieces out of action. By cannibalizing parts, the American gunners minimized the loss, and the next day par' of the 57th Field Artillery Battalion arrived, giving the 7th Division one 155-mm. and four 105-mm. batteries to support what had now become a major defensive effort.

Despite heavy casualties, the Japanese mounted two more attacks on consecutive nights. Not until the morning of 27 November were American troops able to take the offensive, counting at the time some 400 enemy dead outside of their perimeter and discovering over 100 more along with 29 abandoned machine guns as they advanced farther northwards that day. The 7th Division soldiers dubbed the successful defense of the Damulaan area "the Shoestring Ridge battles" after the precarious supply system that supported them rather than after the terrain fought over.

After a few days' rest and a rotation of units, General Arnold finally began in earnest his advance toward Ormoc with a novel tact tic. On the night of 4 December vehicles of the 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion put to sea and leaped-frogged north along the coast 1,000 yards ahead of the ground units. The next morning, the tanks moved to within 200 yards of the shore and fired into the hills in front of the advancing 17th and 184th regiments. This tactic proved effective, greatly disorganizing the defenders, except where ground troops encountered enemy pockets on reverse slopes inland, shielded from the offshore tank fire.

As the 7th Division pushed north with a two-regiment front, the 17th Infantry inland encountered heavy enemy fire coming from Hill 918, from which the entire coast to Ormoc City could be observed. It took two days of intense fighting against enemy units supported be

mortar and artillery fire for the 17th and 184th regiments to clear the strongpoint, after which the advance north accelerated. By 12 December, General Arnold's lead battalion was less than ten miles south of Ormoc City.

While the advance on Ormoc continued events both alarming and reassuring occurred at other locations on Leyte. In early December, elements of the Japanese 16th and 26th Divisions in the central mountains combined with the 3d and 4th Airborne Raiding Regiments from Luzon to attack the airfields in the Burauen area, which the 7th Division had taken in October. Some 350 Japanese paratroopers dropped at dusk on 6 December, most of them near the San Pablo airstrip. Although the Japanese attacks were poorly coordinated, the enemy was able to seize some abandoned weapons and use them against the Americans over the next four days. Hastily mustered groups of support and service troops held off the Japanese until the 11th Airborne Division, reinforced by the 1st Battalion, 382d Infantry, and the 1st and 2d Battalions, 149th Infantry, 38th Infantry Division, concentrated enough strength to contain and defeat the enemy paratroops by nightfall of 11 December. Although the Japanese destroyed a few American supply dumps and aircraft on the ground and delayed construction projects, their attacks on the airfields failed to have any effect on the overall Leyte Campaign.

Meanwhile, on the west side of Leyte, the XXIV Corps received welcome reinforcements on 7 December with the landing of the 77th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Andrew D. Bruce, three and a half miles south of Ormoc City and one mile north of 7th Division positions. The 77th Division's 305th, 306th, and 307th Infantry Regiments came ashore unopposed' although naval shipping was subjected to kamikaze air attacks. As the newly committed unit landed and moved inland' the 7th Division resumed its march north, and the defenders were quickly squeezed between the two forces.

The commitment of the 77th Division proved decisive. As soon as he learned of the new American landing, General Suzuki ordered those forces then attacking the Burauen airfields to break contact and cross the mountains to help hold Ormoc Valley. Only small groups of these troops, exhausted and malnourished' reached the west coast in time to be of any great use. The strongest opposition facing the 77th Division came from a force of about 1,740 soldiers, sailors, and paratroops at Camp Downes, a prewar Philippine constabulary post. Supported by the 305th and 902d Field Artillery Battalions, General Bruce's troops pushed through and beyond Camp Downes to enter Ormoc City on 10 December, just three days after landing. In the final

drive on Ormoc, the 77th Division killed some 1,506 enemy and took 7 prisoners while losing 123 killed wounded and 13 missing.

With the entrance of the 77th Division into Ormoc City, the XXIV Corps and X Corps stood only sixteen miles apart. In between, the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment, with its defenses anchored on a blockhouse less than a mile north of the city, represented the last organized Japanese resistance in the area. For two days the enemy positions resisted heavy artillery fire and repeated assaults. Finally, on 14 December, the 305th Infantry, following heavy barrages from the 304th, 305th, 306th, and 902d Field Artillery Battalions, and employing flamethrowers and armored bulldozers, closed on the strongpoint. Hand-to-hand combat and the inspiring leadership of Capt. Robert B. Nett cleared the enemy from the blockhouse area. For leading Company E, 2d Battalion, 305th Infantry, forward through intense fire and killing several Japanese soldiers himself, Captain Nett was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Once out of the Ormoc area, the 77th Division rapidly advanced north through weakening resistance. Moving along separate axes through Ormoc Valley, its three regiments took Valencia airfield, seven miles north of Ormoc, on 18 December, and continued north to establish contact with X Corps units

At the northern end of Ormoc Valley, the 32d Division had met continued determined opposition from the defending 1st Division along Highway 2. Moving south past Kilay Ridge on 14 December, General Gill's troops entered a heavy rain forest, which limited visibility and concealed the enemy. Because tree bursts in the dense foliage reduced the effectiveness of artillery, assaults were preceded by massed machine-gun fire. Troops then used flamethrowers, hand grenades, rifles, and bayonets to scratch out daily advances measured in yards. In five days of hard fighting, the 126th and 127th Infantry advanced less than a mile \south of Kilay Ridge. On 18 December, General Sibert ordered the 1st Cavalry Division to complete the drive south. The 12th Cavalry Regiment pushed out of the mountains on a southwest track to Highway 2, then followed fire from the 271st Field Artillery Battalion to clear a three-mile stretch of the road. Contact between patrols of the 12th Cavalry and the 77th Division's 306th Infantry on 21 December marked the juncture of the U.S. X and XXIV Corps and the closing of the Sixth Army's pincer maneuver against Ormoc Valley.

While the 77th and 32d Divisions converged on the valley, the 11th Airborne Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph M. Swing, had moved into the central mountain passes from the east. After estab-

lishing blocking positions in the southern Leyte Valley on 22-24 November, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment pushed farther west into the mountains on the 25th. After an arduous advance through steep gorges and hills, heavy rains, and enemy pockets, the regiment reached Mahonag, ten miles west of Burauen, on 6 December, the same day Japanese paratroops landed at the Burl and San Pablo airfields. On 16 December, the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry, moved into the mountains from the Ormoc Bay area to meet the airborne regiment and assist its passage westward. The 2d Battalion made slow but steady progress first through stubborn enemy pockets and at higher elevations, the same nearly impassable terrain that was slowing the airborne troops. But on the 22d3 after two days of battling scattered Japanese defenders on ridges and in caves, the 7th Division infantrymen met troops from the 2d Battalion, 187th Glider Infantry Regiment, which had passed through the 511th, to complete the cross-island move. Seven weeks of hard fighting through the central and northern mountains had come to an end and the defeat of Japanese forces on Leyte was now assured.

The successful X Corps drive south from Carigara Bay and the XXIV Corps drive north through Ormoc Valley and across the island left only the bypassed mountains west of Ormoc Valley under Japanese control. Most enemy troops in that sector were from the 5th Infantry Regiment, but remnants of at least four other units had also made their way there. These surviving troops were in poor condition, having to subsist largely on coconuts and grasses, and their numbers had been slowly reduced by disease and desertion. To destroy this final pocket of Japanese resistance, Krueger ordered the 77th Division to clear the road connecting the northern Ormoc Valley and the port of Palompon on the northwest coast, while to the north and south other units policed up remaining Japanese forces along the coast.

General Bruce opened the drive on Palompon by sending the 2d and 3d Battalions, 305th Infantry, with armor support, west along the road on the morning of 22 December. The 302d Engineer Battalion followed repairing and strengthening bridges for armor, artillery, and supply vehicles. Assault units progressed rapidly through sporadic enemy fire until they hit strong positions about eight miles short of Palompon. To restore momentum, General Bruce put the 1st Battalion, 305th Infantry, on Navy landing craft and dispatched it from the port of Ormoc to Palompon. Supported by fire from mortar boats of the 2d Engineer Special Brigade and from the 155-mm. guns of the 531st Field Artillery Battalion, the infantrymen landed at 0720, 25 December, and secured the small coastal town within four hours.

Learning of the seizure of the last port open to the Japanese, General MacArthur announced the end of organized resistance on Leyte. But Japanese defenders continued to fight as units until 31 December.

Farther north, other American forces made faster progress against more disorganized and dispirited enemy troops. Elements of the 1st Cavalry Division reached the coast on the 28th, and two days later met patrols of the 32d Division. Also on the 28th, companies of the 34th Infantry, 24th Division, cleared the last enemy positions from the northwest corner of Leyte. On 26 December, as these sweeps continued3 General MacArthur transferred control of operations on Leyte and Samar to the Eighth Army. Although Japanese forces no longer posed a threat to American control there, the mop-up of stragglers continued until 8 May 1945.

The campaign for Leyte cost American forces a total of 15,584 casualties, of which 3,504 were killed in action. In their failed defense of Leyte, the Japanese lost an estimated 49,000 troops, most of them combat forces. Although General Yamashita still had some 250,000 troops on Luzon, the additional loss of air and naval support at Leyte so narrowed his options that he now had to fight a defensive, almost passive, battle of attrition on Luzon, clearly the largest and most important island in the Philippines. In effect, once the decisive battle of Leyte was lost, the Japanese themselves gave up all hope of retaining the Philippines, conceding to the Allies in the process a critical bastion from which Japan could be easily cut off from her resources in the East Indies and from which the final assaults on the Japanese home islands could be launched.

The campaign for Leyte proved the first and most decisive operation in the American reconquest of the Philippines. The Japanese invested heavily in Leyte, and lost. The campaign cost their army four divisions and several separate combat units, while the* navy lost twenty-six major warships, and forty-six large transports and merchantmen. The struggle also reduced Japanese land-based air capability in the Philippines by more than 50 percent, forcing them to depend on suicidal kamikaze pilots.

For the U.S. Army, the results of the campaign were mixed. The fight for Leyte lasted longer than expected, and the island proved difficult to develop as a military base. These and other setbacks had their basis in several intelligence failures. Most important, MacArthur's headquarters had failed to discern Japanese intentions to fight a deci-

sive battle on Leyte. Thus, not enough covering air and naval support was available to prevent the substantial enemy troop influx between 23 October and 11 December. This reinforcement, in turn, lengthened the fight on the ground for Leyte and forced the commitment of units, such as the 11th Airborne Division, held in reserve for subsequent operations. Of course, an ever present factor was the dedication of the individual Japanese soldier, the tactical skills he displayed in defensive warfare, especially in using the difficult terrain to his own advantage, and the willingness of his commanders to sacrifice his life in actions that had little chance of being decisive.

In their first combat test, the U.S. field army and corps headquarters generally performed well, with only a few notable errors. One error concerned the attack of the 2d and 3d Battalions, 21st Infantry, during the typhoon of 8-9 November; the effort wasted troop energy and morale in conditions that made a coordinated assault nearly impossible. In contrast, the XXIV Corps' use of amphibious assaults during the campaign showed both innovation and flexibility. But there were also shortcomings at the tactical level. Unit leaders, for example, discovered many problems with available maps, which had distance discrepancies as high as 50 percent. Patrolling and interrogations compensated only partially for such inadequacies, and the thick vegetation and inclement weather limited the value of aerial reconnaissance.

One of General Krueger's operational decisions has also been a topic of considerable debate. His 4 November order for X Corps to remain on the north coast of Leyte to counter a possible Japanese amphibious assault rather than immediately beginning the southward advance through the mountains toward Ormoc gave the recently arrived Japanese 1st Division two days to strengthen its defenses. Had the advance taken place earlier, the X Corps might have taken the defenders of Breakneck Ridge by surprise and avoided the typhoon as well. But the unpredictable nature of the Japanese defenders-from their use of kamikazes and airborne units to the commitment of almost their entire surface fleet without air cover-was underlined repeatedly during the campaign, at times making caution appear the wisest American course of action.

Supply problems also plagued the Sixth Army throughout the campaign. They actually began weeks before the invasion, when the two-month acceleration of A-day resulted in the disorganized loading of transports in staging areas. This in turn caused a disorderly pile-up on beaches of items not yet needed as troops searched for supplies of more immediate importance. In addition, enemy resistance on A-day forced the diversion of the 24th Division's LSTs to

The progress of combat operations inland raised new problems as the distance between combat units and beach depots steadily increased. Many were solved by a combination of innovation and labor-intensive methods, but more effective solutions would have to await development of better air and ground delivery systems as well as the organizational reforms necessary to accommodate them.

The largest single category of problems, however, were those the engineers dealt with during the continuous struggle with terrain and weather. Despite long U.S. Army experience in the Philippines, Sixth Army construction planning proved deficient. Most areas thought to be ideal for airfield and road development, especially those in the southern Leyte Valley, proved too wet to sustain traffic. General Casey's ASCOM engineers began work on three airfields-Burl, San Pablo, and Bayug-only to be halted by General Krueger on 25 November when it became obvious they could not be made serviceable. The Japanese had built the Tacloban airfield3 but in order for the Fifth U.S. Air Force to make full use of it, the engineers had to undertake a huge landfill operation to redirect and lengthen the runway. In the end only one new airfield was built on Leyte-at Tanauan on the east coast, the initial site of Sixth Army headquarters. Moreover, this project necessitated moving and rebuilding General Krueger's command post.

The situation was not much better for road construction. The best existing routes were gravel, and quickly broke down under the weight of American heavy weapons and equipment. The torrential rains of the typhoon season, totaling thirty-five inches in forty days, accelerated their deterioration and delayed all types of construction.

Finally, the slow progress of combat operations ashore also complicated the construction program. As the assault inland and on the west coast continued more engineer units had to be detached from airfield and road construction on the east coast to maintain supply routes, further delaying construction of not only airfields but hospitals, troop shelters, and other projects as well. Thus, as a ready supply base or a stepping stone to Luzon and the other Philippine Islands, Leyte proved less than satisfactory.

Yet, in balance, the Sixth Army's performance on Leyte had more to commend than to criticize. Throughout the campaign Army units demonstrated great skill at amphibious operations and combined arms tactics in challenging terrain and climate. The rotation of combat units ensured that the American ground offensive rarely lost its momentum, while the Japanese Army commanders were never able to concentrate

for anything close to a serious counterattack, despite the size of the combat forces that they committed. The only real threat to the campaign occurred at sea, when the U.S. fast carrier task forces were lured north and the Sixth Army's support vessels lay briefly at the mercy of the Japanese surface fleet.

In the end the Japanese decision to stake everything on the battle for Leyte only hastened their final collapse as they lacked the ability to coordinate the mass of air, ground and naval forces that they committed to the struggle. Even before the fighting on Leyte ended, MacArthur's forces had moved on to invade Luzon and the rest of the Philippines, thereby consolidating their hold on this former Japanese bastion and completing a final major step toward Japan itself.

The official history of the Leyte Campaign has been augmented by many popular and scholarly accounts. The views of senior American ground commanders on the campaign are presented in Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (1964), and Walter Krueger, From Down Under to Nippon: The Story of Sixth Army in World War II (1953). The strategic debate over objectives in the Western Pacific is explained by Robert Ross Smith in "Luzon Versus Formosa," Chapter 21 of Kent Roberts Greenfield, ed., Command Decisions (1960). A readable overview of the campaign is Stanley L. Falk, Decision at Leyte (1966). In the 1970s, the declassification of cryptanalytic documentation relating to the Pacific war allowed fuller treatment of the intelligence background to the Leyte Campaign. A scholarly example of such is "The Missing Division: Leyte, 1944," Chapter 6 of Edward J. Drea, MacArthur's ULTRA; Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945 (1992). The most extensive treatment of the campaign itself remains M. Hamlin Cannon, Leyte: The Return to the Philippines (1987), a volume in the series United States Army in World War II.

CMH Pub 72-27

Cover: U.S. Navy landing craft unload supplies.

(National Archives)

macdonaldanderser.blogspot.com

Source: https://history.army.mil/brochures/leyte/leyte.htm

0 Response to "The Battle of Leyte Gulf Underscored Japan s Ability to Continue Its Defense of the Philippines"

Post a Comment